Cool Kittens NFT scam: How a “Kitten Coup” reverse rug pull got revenge on the hoaxers.

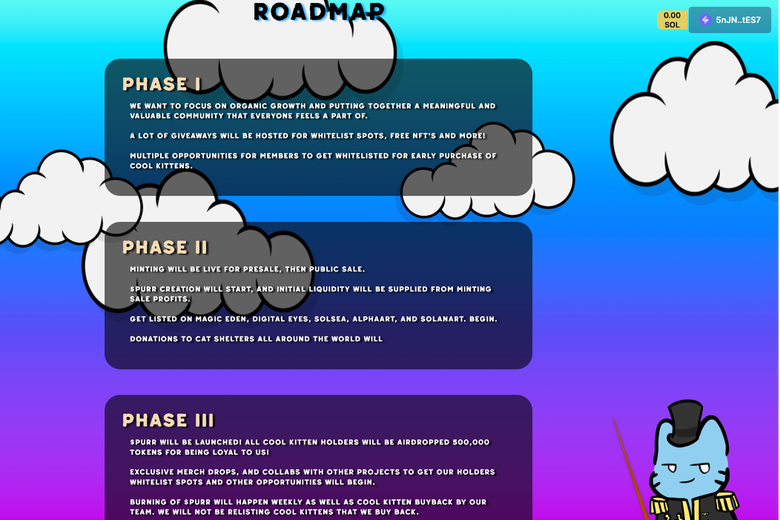

Purchasers of “Cool Kittens” NFTs were promised three things: an electronic token with cat art, a purpose-built cryptocurrency called $PURR, and membership in a DAO, or decentralized autonomous organization, a kind of online community in which NFTs—nonfungible tokens—give each member voting power. In theory, a DAO can make decisions to take on projects just like any collective or corporation might; in the case of Cool Kittens, ideas included distributing physical swag and giving money to cat shelters.

It sounded nice. None of it happened.

Less than three weeks after announcing Cool Kittens NFTs on Twitter, “minting” began on the Solana blockchain, and the cats went up for sale. Within hours, 2,216 NFTs had sold for roughly $70 each. A tidy sum of around $160,000, gathered via crypto, from a global audience. Whoever those buyers were—genuine fans of the feline avatars, or speculators betting that secondary-market sales would be higher than the mint price—they were invited into a chatroom on Discord.

The forum was buzzing with excitement at first—but something was odd. Some users communicated in botlike cadences, hyping the project and begging others to list their NFTs on the secondary market far above cost. A few people started to ring the alarm. Some users noted that the chatroom was relatively quiet considering it appeared to have more than 25,000 registered users. Many demanded details on the promised $PURR token.

A user named Yosan, who lives in the U.K. and works from home as a call-center agent, was an early minter of Cool Kittens. (He and other users I interviewed for this article agreed to speak if identified only by their handles.) He spent about $225 to buy three of the NFTs. “Honestly, I liked the art. The developer was charismatic and talkative, which drew me in, I randomly stumbled upon the project.” He says that, despite red flags, he remained hopeful until it was too late.

After the Cool Kittens NFT developers promised a marketing campaign and the distribution of the specialized cryptocurrency to those who had bought the NFT, the chatroom was suddenly deleted. The founders disappeared. If this had been Petco, kitten buyers would have asked for the manager and gotten a refund. On the internet, there is no manager except for the code that operates the blockchain and the decentralized applications (or “DApps”) that run on it (including the programs that mint NFTs).

This was a rug pull: a scam in which NFT-makers—often after making big promises (e.g., developing an NFT-based game, distributing a token, creating a DAO, redistributing profits)—stop developing a project and disappear with the money—in this case about $160,000 from the sale of the 2,216 NFTs. The hoaxers were successful because they promised incentives to buyers, and they manufactured the illusion of popularity through chatbots and paid Twitter followers. This is happening more and more with NFTs, and three NFT developers whom I interviewed for this article believe there are groups of developers that repeatedly pull off this kind of stunt on unsuspecting NFT buyers.

Today’s NFTs are communities of speculation, fandom, friendship, exclusivity—and sometimes bullshit.

It’s hard to say exactly how big the NFT market is because NFTs are created and traded on many of the more than 15,000 cryptocurrencies out there. The sector, though, is huge and rapidly growing. In 2021, tens of billions of dollars were spent buying NFTs. Those who buy NFTs are in part making a bet that tomorrow’s internet will run on the decentralized, programmable networks of cryptocurrency and blockchain—not the privatized and enclosed platforms of today. In a way, when it comes to PFP (or profile picture) projects, users are purchasing a wardrobe for this future. With a project like Cool Kittens—at least the way it was pitched—it’s a wardrobe with perks.

Here’s the simple version of what this future looks like right now: Cryptocurrencies live on a blockchain, a decentralized ledger of transactions that updates at regular intervals. Most ledgers are made up of sequential blocks, like entries on a spreadsheet. Each block is a record of transactions. Transactions are things like the transfer of cryptocurrency between accounts, or the indexing of data like videos, pictures, songs, or even land deeds, debt, and shares of a company. When an NFT is created, data are recorded onto the blockchain, and a token is minted to represent that data. NFTs, then, represent both real-world and digital assets through electronic tokenization. Minting is the term used when an NFT is initially created and saved onto the blockchain. Once an NFT is on the blockchain, it can be bought and sold. Using Twitter, the popular gaming chat service Discord, and the various websites that function as NFT marketplaces, NFT developers and buyers hype up their projects and trade their NFTs. In the case of Cool Kittens, buyers believed they might be able to resell their NFTs at a profit, or hold them and receive a distribution in the form of the custom $PURR cryptocurrency. Despite growing interest by government regulators into tokens as securities, the issuing of these bespoke currencies alongside NFTs is increasingly common.

So even the simple version reveals something complicated and unruly. The Cool Kittens scam and its surprising aftermath illustrate just how dizzying and dangerous it can all be—but also, that it can be redemptive, too.

Every coup needs a leader. When red flags were beginning to pop up in the Cool Kittens Discord, a user going by Lalalala began posting dire warnings that the NFT project was a rug pull. Once Lalalala, who remains pseudonymous, began pointing out the signs of a scam, they were hard to miss.

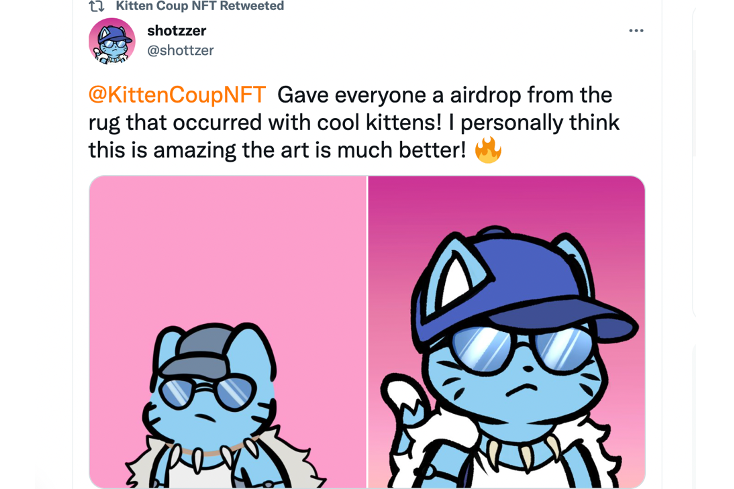

Lalalala quickly assembled an ad hoc team from whoever was in the chatroom and did something unprecedented—a “reverse rug” to flip the rug pull. They moved quickly. Within five days, they recruited a developer to take a digital snapshot of the addresses that had purchased the scam NFTs. Nyaumon, an NFT artist, quickly designed art for more than 2,000 Cool Kittens, and the new project was named “Kitten Coup.” The coup team reached out to the largest secondary trading marketplace and negotiated the delisting of the scam NFTs, so resale royalties wouldn’t continue to enrich the scammers. Then, with the help of that digital snapshot of the NFTs, Lalalala fronted more than $7,000 to automatically redistribute 2,216 new coup NFTs to buyers of the scam NFTs.

Coups can be helped along by the artistic avant-garde, and the Kitten Coup lucked out big time. As the scam NFT developers deleted chatrooms and covered their tracks, the reverse rug group sought to design new art. Many of the buyers of the scam NFT didn’t realize that the artwork was in fact a poor rip-off of another NFT project called Cool Cats, taken from another blockchain; Cool Cats NFTs regularly sell on secondary markets for more than $30,000 each.

Relatively new to NFTs, Nyaumon has been working as a full-time artist since the early 2000s. Originally a designer for the marketplace-style game Neopets, Nyaumon recently began exploring and making art for NFTs. When she heard about the NFT scam, her first reaction was to offer help. “By hanging around on Discord, I learned how tightknit and passionate the NFT communities are. … I was informed about what had happened, and wanted to help. Seeing the old art, I wanted to improve it, make it cuter, and way more unique.”

Imagine buying a scam product and then deciding to take over the scammer’s business to make things right. That’s what Lalalala’s team did. Why bother? The answer gets to the heart of NFTs’ appeal: fervent online communities that are simultaneously about profit seeking and social camaraderie. NFT_Thor, an Italian chemist, was one of the first to join the coup. He had watched the resale value of his freshly minted Cool Kittens NFT drop from $70 to $7 over a few hours. He told me, “Tell your audience that those evil NFT developers are probably on the beach sunbathing in Belize.” This was revenge.

The Kitten Coup organizers are by no means jaded with crypto’s potential after being scammed. MistyBayou, a coup co-founder who worked in software in the U.S. banking industry before becoming a crypto developer, told me: “Cryptocurrencies offer an alternative vision. … I’ve always felt that the internet was designed as a ‘great leveler,’ to tear down barriers between people. It democratized so many fields, allowing anyone with talent to become a writer, an artist, a musician, but finance stayed centralized and if anything, only became more so with the dominance of credit card processors and PayPal.” As a DeFi (for “decentralized finance”) freelancer, Misty works on the blockchain systems and programs that make cryptocurrencies and their DApps work. As Misty watched the NFT scam unfold, they saw a chance to help other members of their community—and become an NFT project founder themselves. This hadn’t been the first time they’d seen NFT developers promise big and not deliver. For Misty, the NFT scam was an opportunity to counter an injustice while growing their own online persona and brand.

One thing that struck me while reporting this story was the idea that even though you tend not to know anyone else’s birth name, crypto and NFT spaces aren’t actually anonymous—they’re pseudonymous. As Misty stressed, there’s a big difference between cultivating and using an online brand and plain old anonymity, and the difference is at the heart of how online crypto spaces work. “Pseudonymity is an old idea, authors have used pen names for a variety of reasons for centuries, but that pen name still has longevity and achievements attached to it.” In other words, there are two realities in NFTs and crypto more generally. The first consists of people who use the anonymity of the internet to swindle others out of their money and skirt accountability. They generate hype, and they’re good at it. When the time for transparency comes, they simply delete their profile. In this sense, it’s the Wild West, a kind of internet wildcat drilling that preys upon those who are susceptible to the hype and are all too keen to speculate. That’s what the NFT scammers are about. On the other hand, some take up pseudonyms—online identities, profiles—and then build street cred around that persona. For Misty, “no one judges you by your race, religion, or gender if you’re just a cat with a weird name. The first impression in crypto spaces then is in the way you express your ideas, and the quality of those ideas.” So it’s the old notion of the marketplace of ideas, but with cute avatars. Is that what it takes for such a utopian concept to work?

Some say yes, and see NFT communities as the first step toward something much larger. To Yosan, who became one of the coup’s community moderators, NFTs are about investment and community: “They are digital art that allow someone to be part of a community and are investments for when the world will go digital in the future.” NFT_Thor, the Italian chemist, said, “At the end of the day, we are dealing with .jpegs: the value of the object is what we give it through our community.” NFT communities are increasingly using coded “smart contracts” to collectively choose investments, fund charities, distribute royalties, and make community decisions in a framework where “one NFT equals one vote.” The Kitten Coup has kept busy: It is in the early stages of organizing itself as a DAO, is developing coding tools to help other NFT developers “reverse the rug” if they get ripped off, and is also releasing a biweekly comic strip illustrated by Nyaumon.

NFT communities are experimenting with ways to tap the theoretical security, transparency, and decentralization of blockchain structures to create decentralized autonomous organizations. One of the broken promises of the scam NFT developers was a DAO. An increasing number of NFT projects promise DAOs. Almost all are snake oil, a hype tactic. But a few NFT projects are experimenting with code and platform to design decentralized, electronic organizations in ways that are poised to innovate the way groups of all kinds make decisions.

Daren McKelvey, a blockchain business development expert and head of growth at Nodle, sees DAOs as experiments in ways to do governance better, be that governance of NFT crypto communities or previously nondigitized institutions. He sees the potential for “programmed governance” to touch all facets of social life, including innovating governance to make it more responsive to collective needs and desires. He says, “I’m long on DAOs and excited to see how they start to play out in changing life as we know it.”

There are plenty of complications that the designers of DAOs must contend with. For DAOs that desire a “one person, one vote” system, there’s no simple way to confirm that one crypto wallet equals one person, since anyone can generate multiple wallets. In contrast, DAOs that want to measure stake in a project by number of NFTs held have to contend with the possibility of a monied interest buying up the supply and overwhelming collective goals in order to get their way. Finally, DAOs can be seen as signifying the financialization of social life (though I’d say it’s unfair to say DAOs are any more nefarious than social media platforms that monetize users as data creators, or where the collecting of likes and retweets is akin to the accumulation of capital).

Could the future of democratic governance for nonprofits, corporations, and even governments be germinating in odd and chaotic online NFT communities? DAO governance is only as good as the coding, and there are certainly limits to programmed governance. NFT communities are pushing those limits in their experiments with programmed governance, in their search to create global, inherently censorship-resistant communities in the digital age. Misty remains optimistic: “I am a bit of a utopian at heart. I believe in a monetary system without gatekeepers and a system of business with lower barriers to entry. I believe in true cross-border reality. I think the fact that four people can meet each other and start a small socially beneficial business within a week is a really powerful thing. We’re so used to this rigid economic and social order. Anything that tears at that and puts ‘the little people’ in charge has to be a good thing long term.”

What stands in the way? For one thing, if you’re outside this world, you may be skeptical of innovations in governance coming from a bunch of strangers with cat avatars. The seemingly endless scams and grifts certainly don’t instill confidence in a vision of an internet without central authority. Plus, there’s a lot of stupid money being thrown around. But what’s going on in cryptocurrency is more than just new forms of conspicuous consumption plus online chatrooms with pay-to-play access and pretty pictures. Beautiful things can come out of working with strangers in a cryptographically transparent voting organization, the least of which include new ways of collaborating, adorable kitty art, and sweet, sweet revenge.

This content was originally published here.