The Biggest NFT Video Game’s Economy Is Collapsing Because NFT Games Don’t Work

The biggest NFT game currently in the marketplace is Axie Infinity, a game—similar to Pokémon—in which players collect and battle monsters which resemble axolotl salamanders.

The business model for Axie Infinity and nearly all other nonfungible token (NFT) games is called “play to earn.” In these games, all players must start by purchasing NFT characters on a marketplace. In-game assets and currencies are traded on crypto exchanges, so everything in the game is worth money. The often-high upfront cost of buying into the game is theoretically justified by the opportunity to earn money by playing.

Web3 investors are really excited about the prospects of games like this. Reddit co-founder Alexis Ohanian, who is an investor in Axie Infinity, believes play-to-earn games will be 90 percent of the gaming market in five years. And Sky Mavis, the developer that makes Axie Infinity, had the good fortune to be years ahead of the competition. Their NFT game launched in 2018, and they were live and operational when NFTs exploded in popularity and investors decided to bet that the blockchain was the future of gaming.

As a result of being first movers in the space, this once-tiny independent studio was able to raise $150 million in financing in October 2021 at a valuation of $3 billion. Around the same time, Sky Mavis trumpeted its game’s tremendous subscriber growth, which exploded in the third quarter of 2021 to over two million daily active users. In December, Axie Infinity Shards (ASX), the game’s governance token, had a market capitalization larger than that of the French games publisher Ubisoft, which makes the Assassin’s Creed, Far Cry, and Watch Dogs games. In July, a single rare Axie monster sold for 369 ether, worth over $800,000 at time of sale. A rare plot of land in the game sold for 550 ether ($2.5 million) despite the fact that the gameplay features using in-game land are not yet available.

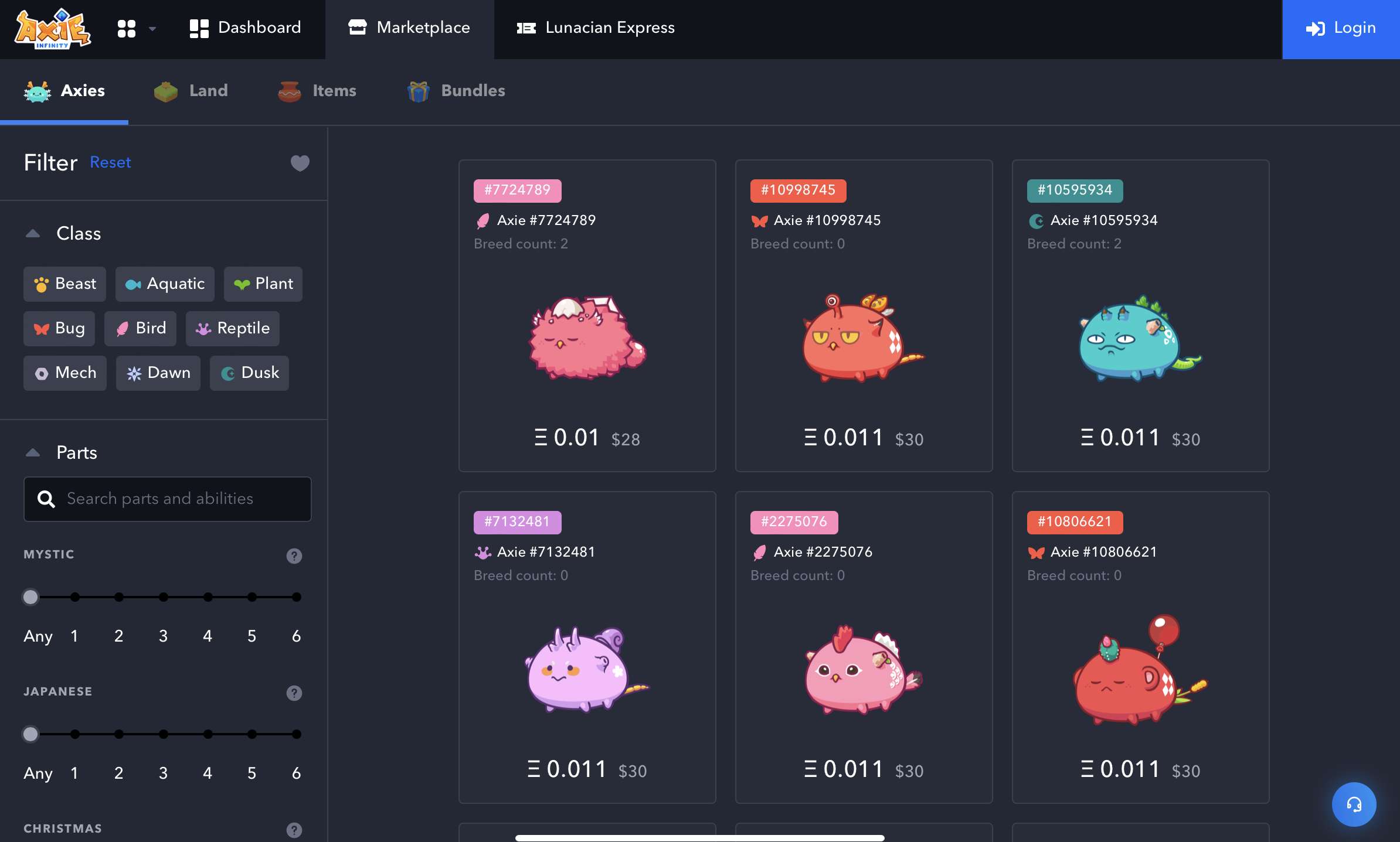

However, some big problems have emerged in Axie Infinity: The value of an in-game currency called Smooth Love Potions (SLP) crashed from last summer’s high, above $0.40, to a value of around $0.01 in January 2022, lower than its price a year earlier when few people had heard of NFTs and the game itself had only about 50,000 active players. This is a big problem for Axie Infinity, because the object of the game is “playing to earn” and SLP is the currency you earn by playing. As a result of plunging values, the volume of transactions for Axie assets may have fallen as much as 70 percent from its peak in just a couple of months. The floor price of the cheapest Axie characters fell to around $30 in January 2022, which signals that users are dumping their assets, since it often costs more than that to mint one of the characters. AXS, the governance token, has lost over 40 percent of its value since Christmas, a paper loss of billions of dollars.

By looking at what’s going wrong with Axie Infinity, we can see how the play-to-earn business model has major problems with no clear solutions.

Gaming NFTs Aren’t Like Other NFTs

NFTs are unique tokens on a blockchain that are attached to digital assets, often images. In some cases, these images are works of art, and the holder of the token is considered the owner of the digital work. In other cases, the NFT serves as a key or a club membership. For example, the popular Bored Ape Yacht Club NFT collection has exclusive Discord chat groups where Ape owners can network with celebrities and crypto influencers. The Bored Ape team has airdropped new NFTs as free gifts to owners of its original NFT collection, and hosted a live Ape Fest event in New York in summer 2021 with parties only Bored Ape owners could attend.

Whether these perks justify the eye-popping prices these NFTs trade at is subject to dispute, but there is an argument that the prices of the most coveted NFTs are justified by the possibility of valuable airdrops or other benefits. These are speculative investments and the people buying them have theories about why they might be more valuable at some future date than they are today. The Apes were looking smart in January 2022, as the floor price for the cheapest assets in the collection continued to climb while the broader crypto sector hemorrhaged more than $1 trillion dollars.

But play-to-earn gaming NFTs are seeming a lot dumber. They’re not works of art. They’re not club memberships. They’re not status symbols. They are items in a video game, and the video game is about money. The NFT characters are valuable because they can earn you money. So, the value of the NFT is based on its ability to produce video game resources that also have monetary value: How much can it earn you in the pay-to-earn game? How fast can your initial investment pay for itself and start earning you profits through gameplay? And what happens to your investment if your expectations about these things are wrong?

Here’s how it’s supposed to work.

The Axie Economy

The resources in Axie Infinity as it currently exists are: Axie monsters; AXS cryptocurrency, some of which is awarded as a prize to the top handful of competitive players, but which all other players can only acquire by purchasing it; and SLP, which is an in-game reward currency also traded on crypto exchanges. The way players are supposed to earn money in the game is by selling their extra SLP for cash.

An Axie monster is kind of like a Pokémon, and Axie battles are similar to Pokémon battles, but each monster is connected to a token and can be sold on crypto exchanges. To play the game, you need at least three of them, and you have to start by buying your monsters for real money from other players—there’s no Pokémon professor to give you a starter monster, and you can’t catch anything in the game.

New Axies are only produced by “breeding” existing Axies. When two Axies are bred, they produce an egg which will hatch after 5 days into a new NFT monster with a mix of characteristics inherited from the parents, and possibly some random mutations. Breeding Axies costs a fee that must be paid in AXS tokens as well as a variable amount of SLP depending on how many times the parent Axies have produced offspring previously.

So, in order to produce a new NFT character, you have to pay a fee that is usually between $30 and $80 in crypto, depending on the current price of AXS, as well an amount of SLP representing hours of time spent playing and worth what has, at certain points, been a significant amount of real money. Producing the offspring also depreciates the value of the parent Axies, because the SLP cost of breeding an Axie rises each time it is bred, and after breeding seven times, Axies can no longer produce offspring.

The most important things to know about Axie breeding is that it is a costly and risky activity, and it is the only activity in the game that removes SLP currency from circulation.

SLP is an “uncapped utility token,” which means it is a cryptocurrency that is awarded for completing tasks in the game, and there is no limit on how much of it can be produced. Nearly all the game’s rewards are paid in SLP. This is a fancy way of saying it’s an in-game currency like gold in World of Warcraft or bells in Animal Crossing.

Players earn SLP from winning battles against other players in the game’s arena mode and for clearing levels filled with computer-controlled enemies in adventure mode. Every player can earn 100 SLP each day from adventure mode and an additional 50 SLP for completing a daily quest which requires completing some adventure levels and winning some arena games. Above that threshold, more SLP can be earned from winning arena matches, and the amount of SLP awarded for an arena win varies depending on how highly-ranked the player is. Average to decent players will get 6 to 12 SLP per win, while the top players can earn as much as 24 for each victory.

The reward for collecting powerful (and therefore expensive) Axie monsters and being in the top few percent of players is that you get more SLP for winning arena matches. Everything in the game is rewarded with SLP and the benefit of progress (or spending lots of money) is the ability to get larger amounts of SLP for time spent playing. Getting as much SLP as you can is the object of the game. So, if SLP is worthless, then so are the NFT assets which are valued because of their SLP-earning ability.

A player with a basic team of monsters, getting modest rewards from arena wins with an average ranking can earn about 220 SLP per day, playing for about three hours. A highly ranked player can earn over 800 SLP if they play for six or eight hours. At a valuation of $0.35 per SLP, the 220 SLP the casual player can earn is worth about $75. If SLP is worth $0.01, 220 SLP is worth only $2.20.

Why Did SLP Crash?

Here’s how “play to earn” works in the real world: Over 40 percent of all active Axie Infinity players are in the Philippines, where the per capita GDP is about $3,300 per year. The second highest concentration of Axie players is in Venezuela, where the economy has been in complete collapse since 2013 and the local currency has been rendered near-worthless by hyperinflation. Only about 6 percent of Axie Infinity players live in the United States. It has been difficult for games like Axie Infinity to acquire players in the developed world because many gamers despise NFTs and these games look and play like free-to-play phone or browser apps, but require players to buy hundreds of dollars worth of NFTs to get started.

Most players in the global south gain access to the game through “scholarships,” arrangements in which a manager—sometimes a player in the developed world with a large stable of extra monsters, and sometimes a crypto investor who is speculating on Axie assets—loans a player a squad of Axie monsters to play with in exchange for a cut of their SLP earnings. “Scholars” aren’t looking to amass large collections or climb the competitive ladder. They’re not really approaching Axie Infinity as gamers or investors—they’re being hired as laborers. They harvest the roughly 220 SLP a player with a relatively inexpensive team of NFT monsters can obtain each day for grinding out the daily 100 SLP from adventure mode, winning a few arena matches, and earning 50 SLP for completing the daily task. They never breed any new Axies; the currency they earn is always quickly sold off on crypto exchanges.

The appeal of this arrangement for both investors and “scholars” is clear when SLP is worth a lot of money: If playing the game generates $70 worth of SLP per day and the investor takes 30 percent of the proceeds and pays 70 percent to the “scholar,” then the investor gets a $147 weekly return on about a team of NFT characters that might have cost around $800 when the assets were near their peak, and the “scholar” makes $343 per week in a country where the minimum wage is around $7 per day. Players in the Philippines who got into the game when it was booming over the summer of 2021 were able to buy houses with the proceeds of their gaming.

But game economies don’t work like real economies where payments in currency come from a circulating, finite money supply. Instead, in-game currencies are created whenever someone earns a reward—in the case of Axie Infinity, clearing adventure levels, winning arena matches, or completing their daily quests, and game currency is deleted when it is spent on a “sink,”—some activity which induces players to pay the currency back to the game. In Axie’s case, the sink for SLP is breeding new monsters.

Far more SLP is being generated than is being spent on breeding. Only 5 percent of players have ever bred Axies, and only 5 percent of players who have bred Axies do so again in consecutive months. A large percentage of the player base is creating SLP through their gameplay and then shoveling it into the marketplace, while a much smaller sliver of the player base is consuming SLP by breeding Axies. About 250 million SLP are produced each day, while only 50 million are used for breeding. This creates a monthly surplus of 6 billion SLP, a recipe for massive inflation. For a while, speculative investors were snapping up the currency, perceiving it as a cheap way to invest in the future of NFT gaming. But as workers in the developing world learned of the windfalls they could reap from the game and started farming for SLP, the volume of SLP being produced skyrocketed, these investors saw their holdings devalued by the flood of currency pouring into the marketplace.

Even though the game’s player base seemed to boom last fall, the growth was driven almost entirely by new “scholars” in the developing world joining the game to grind SLP to sell on crypto marketplaces, and each of those players was contributing to the oversupply of the currency and driving down its price. Since these players weren’t trying to build large collections, they weren’t creating much demand for new Axies, so there wasn’t incentive for players to breed them. Sky Mavis has attempted to regulate the game economy by increasing the SLP cost to breed while reducing the ASX fee, but it hasn’t been enough to bring supply and demand into equilibrium.

The game’s explosive user growth in 2021 was almost entirely driven by laborers in the developing world using borrowed NFT assets to grind for currency to sell to investors who were investing in the game because they were excited about the user growth. It was a house of cards. And, as the value of SLP produced from completing daily tasks has plunged below the minimum wage in the Philippines, many of those players have stopped logging in.

The Problem With ‘Play To Earn’

For its part, Sky Mavis is touting a number of upcoming features the developers believe will continue to drive growth. They’re preparing a major update to the battle system, a game mode designed around the in-game land assets, and a system for upgrading Axie monsters. All these features will likely provide new in-game uses for SLP currency, thereby increasing demand for it. Sky Mavis co-founder Jeff “JiHo” Zirlin said on Discord that an “experimental sink” for surplus resources will be coming sooner than the major update, and in January Sky Mavis announced a special event allowing players to “release” Axies—permanently deleting their NFT characters—in exchange for cosmetic items that are also tied to NFTs, which players will be able to place on their in-game land in the not-yet-released land gameplay mode. This only briefly propped up the floor price for the least desirable monsters. Statements from the developers have framed the volatility of Axie’s markets as a function of the game’s rapid growth and runaway success.

Additionally, Sky Mavis is planning a revamped experience for new players that lets them use non-blockchain “starter” Axie monsters so players can try the game without having to buy NFT characters, which the developers hope will help attract more new players. In other words, Sky Mavis is dealing with the fact that its current model is unsustainable by turning Axie Infinity into a substantially different game.

The developer’s willingness to make big changes to their game to try to address structural problems has earned plaudits from crypto industry analysts, and Sky Mavis has an enormous war chest of cash from its stakers and investors. When transaction volume was high, Sky Mavis was earning millions of dollars each day from the 4.25 percent of each NFT transaction it collects, so it has the capacity to hire lots of experienced game designers, economists, and other experts to try to solve the problems with its game and build compelling new features.

But with SLP selling below $0.01 and the new game features months away, players are looking at other NFT games in hopes of finding a better return on investment. Some players have been shifting to a horse racing game called PegaXY, which has an economy similar to Axie Infinity’s, with an uncapped in-game currency used to mint new NFT characters. Its main innovation is that it formalizes the “scholarship” arrangements between investors and developing-world players and supports them with “safe” or “trustless” systems that make it easier for players to rent out their extra NFT characters. Since investors’ return under this system is not contingent on the workers being trustworthy or reliable, the terms of “scholarship” arrangements in this game are more favorable to investors. Instead of trying to realign the incentives of the game economy to discourage such behavior, newer NFT games seem to accept that this is how play-to-earn will work, and are trying to make it more lucrative for investors at the expense of laborers.

As the sector evolves toward supporting this kind of play, the optimum strategy for these games is not “playing to earn” and does not even involve playing the games at all. Rather, investors in rich countries will speculate on in-game currencies and assets while outsourcing the actual playing of the game to workers in the developing world who are paid less than $1 per hour to grind for currency until massive inflation caused by oversupply renders the currency worthless, at which point everybody migrates to another game to repeat the cycle and people who are overinvested in the old game’s NFT assets lose a lot of money.

No NFT game developer has yet presented anything that seems likely to solve the fundamental problem of the play-to-earn model: Any time the currency in a video game rises in price so that it has substantial real-money value—whether because of hype surrounding a new game, or investor interest in a title, or because of new features in an existing game like the ones Sky Mavis hopes will reverse the fortunes of Axie Infinity—the demand for the resource creates an incentive for laborers in developing countries to surge into the game in large numbers to farm the currency until the available supply swamps demand and the price tanks again. The market for any currency that is generated as a function of players’ time spent grinding in a game will only reach equilibrium when the price of the currency is valued based on the price of time for the players whose labor is the cheapest, and for players in the developing world, that’s pennies per hour.

And developers can’t control the supply of currency by taking measures to punish the gameplay patterns typical of players in the developing world, because the bulk of the game’s user base would instantly disappear if the developers got rid of them. Such measures would also deter new players from joining the game, because cutting off rewards for people who play like “scholars” would make it difficult or impossible for any player joining the game with a modest collection to earn back their initial investment or expand their collections through playing.

Further, play-to-earn models require constant user growth. The real money economy of a game like Axie Infinity is zero sum—no money is produced inside the game, so the only money anyone can take out of the game is money somebody else has put into it. Everybody’s goal in the game is to make money; they’re all “playing to earn,” but the only players investing more money into the game than they expect to take out of it are new players who have to buy stuff to get started. When there are not enough people buying more than they’re selling, the game economy collapses.

It may be possible to devise a play-to-earn model that rewards casual or less-invested players without creating economic incentives for people to play in ways that inevitably tank the value of the reward currency. But the biggest publishers in gaming have previously tried and failed to figure out sustainable ways to introduce real money into the player-to-player economies of video games, and blockchain technology does nothing to address the reasons previous efforts have failed. NFT game developers and their investors may be underestimating the problems inherent to this business model. The entire “play-to-earn” concept is built on the premise that video game currencies can be stores of real-money value, so if developers like Sky Mavis can’t figure out how to prevent what happened to SLP from continuing to happen to reward currencies, then “play to earn” isn’t going to work.

The post The Biggest NFT Video Game’s Economy Is Collapsing Because NFT Games Don’t Work appeared first on Reason.com.

This content was originally published here.